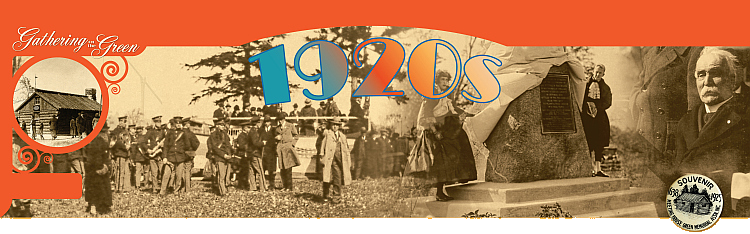

About 1890 Frank H. Fogg leased several acres on the Hampton town green and built his farmhouse there. In 1925 he sold the house to The Meeting House Green Memorial Association, incorporated that year with 76 charter members for the purpose of creating a memorial, on the site of the first meeting house, to honor Hampton's founders. Edward Tuck, a wealthy philanthropist whose English ancestors had been among the first settlers, donated $7,000 to the project. He also contributed to the construction of Tuck Field, which was dedicated in 1930. The Association bought the Fogg house, added a room to display Hampton relics, and built Memorial

(Founders) Park. As an attraction, they built a log cabin on the grounds to represent what they believed was the first meeting house.

The Hall and Park were dedicated on October 14, 1925, the town's 287th birthday. Organized by Hampton Beach businessman George Ashworth, the event featured a parade, a concert, and a banquet at the Carnival Dance Hall. Rev. Ira Jones, the Association's founder and first president, 'invoked the divine blessing' as descendants of Hampton founder Rev. Stephen Bachiler unveiled the bronze memorial tablet that had been mounted into a 12-ton boulder at the park. The first annual meeting was held that day in the log cabin.

Mr. and Mrs. John Bradbury were hired as live-in custodians. They were paid an annual salary of $1,000 plus housing to look after the house and the park and to greet summer visitors to Tuck Memorial Hall.

In 1926, to recognize its historical function, the Association changed its name to The Meeting House Green Memorial and Historical Association.

In 1929 the 'admirable hostess' Mrs. Bradbury reported that the interior of the log cabin had been refinished and furnished 'to look like an early home,' and that two hundred and ten visitors had signed the guest register, 'more than twice the number of the preceding year.' President William Brown reported that the 'Association now numbers 36 members, not counting the towns once a part of Hampton.' At the end of the decade the Association reported $1,057 in the Treasury, of which half was earmarked to pay the custodian's salary. Membership dues were $1.00 per year.

Presidents during the 1920s were Edward Tuck (Honorary), Rev. Ira Jones (1925-1927), and William Brown (1927-1930). When Ira Jones died in 1927 at age 91, the Town and Association dedicated a memorial in his honor on the Tuck House grounds.

No Vociferous Bally-hoo Men

No Vociferous Bally-hoo Men

James Tucker wanted the 'roaring' that was going on in the rest of the country to stay far, far away from Hampton Beach. From the pages of his Hampton Beach News-Guide he informed readers more than once that the beach had a 'reputation for cleanliness that extends from coast to coast. We mean cleanliness as to population as well as in its physical aspects. There are no rattling rides, whirling whips, swirling swings, dizzy drones, silly side-shows or vociferous bally-hoo men.'

Even with Tucker's assurances that 'a splendid class of vacationists has been attracted to this resort,' Federal prohibition agents were certain that Hampton was a main artery for bootleggers running between Boston and Maine. Agents staked out the beach and stopped and searched trolleys and automobiles for illegal liquor. Irate local businessmen felt that the checkpoints hurt the reputation of the beach as a clean, well-kept resort.

'This is where we have to get them, if we get them at all. The business men should be glad that the illicit traffic is being suppressed,' said one agent. It was an open secret that 'great loads of hootch' were offloaded from boats in the Hampton River onto waiting trucks. In 1926 agents captured the motor boat Loretta, loaded with illegal alcohol, when it ran aground in heavy fog at the mouth of the river. It was the first successful bust in the area for the 'booze hounds.'

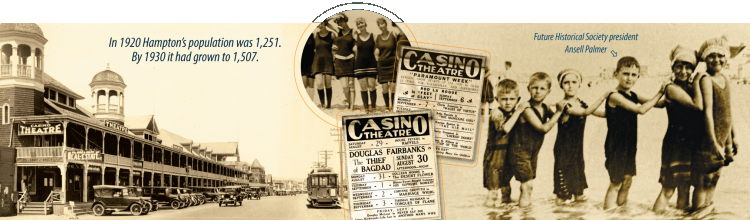

The Street Railway

The decade began with the town's $80,000 purchase of the financially troubled EH&A Street Railway. Since 1897 its electric trolleys had brought over a million visitors to Hampton Beach, and locals relied on it for transportation to school, shopping, and work. But high overhead costs and competition from the automobile resulted in ever-diminishing service, and in 1926 the town abandoned the railway and sold the assets.

Public Services

In this era, public services were becoming regular and professional. Village and Beach shared a fire station and police station at the beach. After a devastating beach fire in 1921, the town enacted building ordinances and appointed a building inspector. Public water, gas, garbage collection, telephones, and motorized snow plowing were available. Public sewers were another matter—sewers at the beach flowed raw waste into the ocean and the Village relied on cesspools and privies.